The Sixth Mass Extinction

Did you know that you're in the midst of the sixth great mass extinction in

Earth's history? Over four billion years, and only six extinctions. It's rather

remarkable that it's happening in your time, don't you think? Or should we not

be surprised?

The greatest irony is undoubtedly that you even have something to do with

it. Oh, I don't want to blame you, necessarily: just by living the way you do,

the way you've been brought up, the way you've been shown, you've been

contributing to the extinction of millions of species. And millions more are

destined for life's trash heap soon.

Perhaps you'd like to know more about how this is happening, and what

you can do to minimize its effects. I want to tell a sad tale about

the Monteverde Cloud Forest, in Costa Rica.

Let's start with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's most recent

predictions (from 2007): "Climate change is likely to lead to some

irreversible impacts. There is medium confidence that approximately 20

to 30% of species assessed so far are likely to be at increased risk of

extinction if increases in global average warming exceed 1.5 to

2.5oC (relative to 1980-1999). As global average temperature

increase exceeds about 3.5oC, model projections suggest significant

extinctions (40 to 70% of species assessed) around the globe." From the IPCC

Synthesis Report 2007.

"Astonishing," I thought, when I first heard it. "Can it really be possible

that we stand by and watch as we eliminate half of Earth's species by our

ridiculous reliance on fossil fuels?" The more I see, the more I believe that

the answer is "Yes!"

So let's see how this might come about in a couple of cases: one I know of

personally; the other comes from the other side of the globe, in Australia.

I went to Costa Rica in the summer of 2011, as part of a class studying the

tropical rainforest and cloudforests there. The cloudforests are particularly

interesting: they're at high elevation, literally "up in the clouds" (as the

name suggests), and feature really interesting biology (such as stunted

rainforest trees -- you feel like you're a giant in a rainforest, because your

head is up in the canopy!).

My aunt Nelle is a great one for bird-watching, and she'd told me to keep

my eye out for a Resplendent Quetzal, which was once commonly found in the

Monteverde Cloud Forest. However, warming climate has meant that the toucan is

moving up, threatening the quetzal. I'll let another friend of the quetzal tell

her story:

Toucans [are] a relative newcomers to the Monteverde area and people who have

been here a long time didn't used to see them. The toucans preferred lower

altitudes. But as the temperatures have increased they moved further up the

mountain. Now they are quite common in Bajo del Tigre. The trouble is that

toucans like to eat eggs and some of the birds up here that are already

threatened, like the three-wattled bellbird and the quetzal make their nests in

tree hollows. They haven't learnt how to protect their eggs from toucans

because they never used to have them around their nests. Toucans love quetzal

and bellbird eggs.

Last year as part of the canopy campaign for the local school some of us spent

many hours on the bridge in the cloud forest reserve watching a pair of

quetzals tending their nest. Two weeks later the tree hollow was torn open and

the nest and the young were gone. No one saw what got the nest but it must have

been pretty strong to tear open even a rotten tree. The last thing bellbirds

and quetzals need is more tragedies like that.

Rowan Eisner

Published as a blog on January 17, 2012,

Friends

of the Rainforest. For a more scientific reference, try

The effects of climate change on tropical birds,

Review Article,

Biological Conservation, Volume 148, Issue 1, April 2012, Pages 1-18

Cagan H. Sekercioglu, et al.: "In Monteverde, Costa Rica, climate change has

already enabled keel-billed toucans (Ramphastos sulfuratus), cavity-nesting

nest predators, to expand their range into the highlands, where they now

compete with the montane forest specialist resplendent quetzals (Pharomachrus

mocinno) for nest holes, as well as preying on quetzal nests (Pounds et al.,

1999)." I met Alan Pounds in Monteverde when I was there.

Sad to say I didn't see any quetzals while I was in Costa Rica. I did see leaf

cutter ants, however, and this surprised our guide. "We're not used to seeing

leaf cutter ants up here," he said. Another recent arrival, and another threat

to endemic species.

|

|

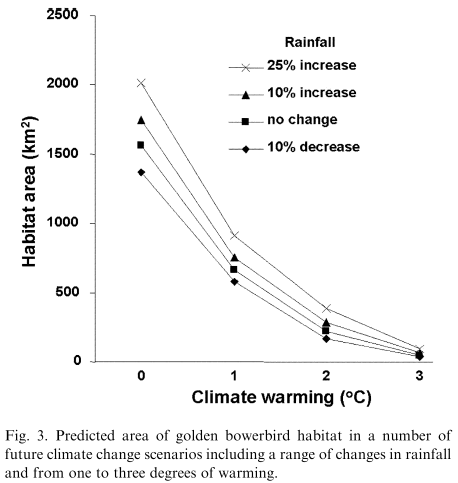

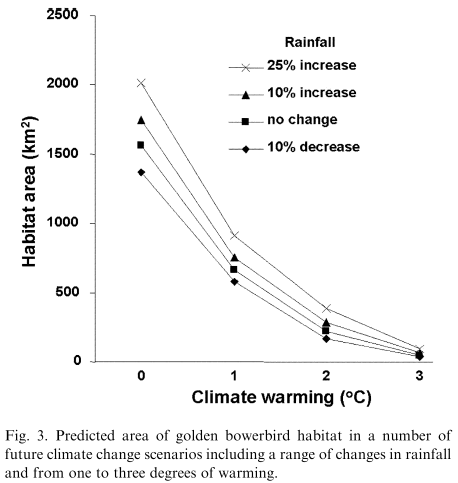

Australia's Golden Bowerbird is another climate-change study, on the other side

of the world: The World Wildlife Fund produced a rather

depressing report entitled "Bird

Species and Climate Change", which included this summary of research on

Australia's golden bowerbird: "The golden bowerbird, along with many other

birds in the Wet Tropics of Australia's northeast, is highly vulnerable to

climate change. Its suitable habitat would decrease 63 per cent with less than

1oC of future warming, up to 98 per cent with 2-3oC of

warming, and completely disappear with between 3 and 4oC of warming,

illustrating why this zone's climate scenario has been termed 'an impending

environmental catastrophe.'"

|

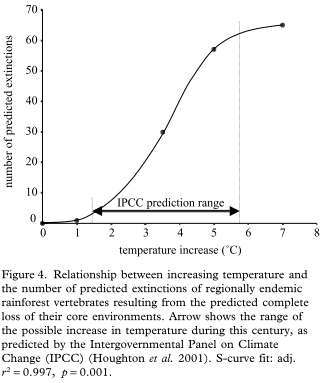

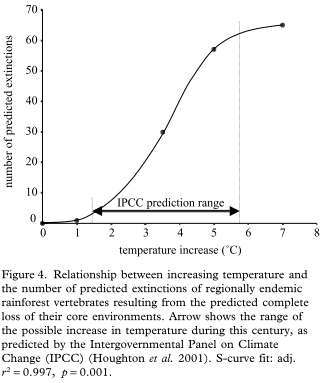

It cites the primary research of Hilbert et al., in "Golden bowerbird

(Prionodura newtonia) habitat in past, present and future climates: predicted

extinction of a vertebrate in tropical highlands due to global warming"

|

|

(as well as the 2003 paper Climate

change in Australian tropical rainforests: an impending environmental

catastrophe -- and that's a title to give anyone pause). The graphic at

right is from that publication, and shows the complete extinction of all 65

endemic vertibrates studied by 7 degrees C of warming.

The World Bank is

operating under the assumption of 4 degrees C of warming by the end of the

century, which would lead to the predicted extinction of about two-thirds of

the species studied.

|

|

It's sometimes hard to be cheery in the face of the climate change news. The

only good news is perhaps the fact that we're aware of the problem. The biggest

question of all is this, from the human perspective: how many species (and

which) can slip away before we, too, become "committed to extinction"?

I often think of Kubler-Ross's "Five Stages of Grief", which she formulated to

summarize typical responses to those learning of a terminal disease. Her

responses ("DABDA") were

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

Why not extend this to our response to climate change? Dr.

Steve Running has done just that. In 2007 he took Kubler-Ross's stages, and

framed them in terms of climate. Here's the short-hand version:

- Denial -- no such thing as climate change

- Anger -- "I refuse to live in a tree house in the dark and eat nuts and

berries." or "Dr. Steve Running is a bloviating idiot!" (for pointing out the

climate change, evidently).

- Bargaining -- "Global warming won't be all that bad -- heating bills will

go down!"

- Depression -- "We are going to be living in tree houses in the dark

and eating nuts and berries!" (if not worse).

- Acceptance -- "exploring solutions to drive down greenhouse gas emissions

dramatically, and find non-carbon intensive energy sources"

As Dr. Running says, however, "[a]n obvious flaw in this analogy is that many

people are simply ignoring the global warming issue, a detachment they cannot

achieve when they are personally facing cancer." But doesn't this simply

suggest that people are still stuck in the denial phase? While not as

personally threatening as terminal cancer, we're facing a potentially

civilization-terminating crisis (back to nuts and berries), if not worse -- a

species-terminating crisis (back to cockroaches eating the nuts and berries):

Links and Notes:

- Evolutionary

Responses to Changing Climate. Davis, M., R. Shaw, and

J. Etterson. Ecology, Vol. 86, No. 7 (Jul., 2005), pp. 1704-1714.

- Extinction risk from climate change. Thomas, et al. 2004. From the abstract:

Exploring three approaches in which the estimated probability of

extinction shows a power-law relationship with geographical range

size, we predict, on the basis of mid-range climate-warming scenarios

for 2050, that 15-37% of species in our sample of regions and taxa will

be 'committed to extinction'. When the average of the three methods

and two dispersal scenarios is taken, minimal climate-warming

scenarios produce lower projections of species committed to extinction

(~18%) than mid-range (~24%) and maximum-change (~35%)

scenarios. These estimates show the importance of rapid implementation

of technologies to decrease greenhouse gas emissions and strategies

for carbon sequestration.

- Extinctions under Scenarios of

Global Climate Destabilization (GCD). Something that I wrote in April of

2010.

- Evolutionary Pressures Resulting

from Anthropogenic Global Climate Destabilization. A follow-up that I wrote

in the fall of 2010.

- Daphne Wysham has added a sixth stage to add to

Kubler-Ross's five: Do THE WORK! The

Six Stages of Climate Grief (a local copy).

- Psychology & Global Climate Change: addressing a multifaceted phenomenon

and set of challenges (a local copy).

Website maintained by Andy Long.

Comments appreciated.