As you celebrate America

Recycles Day each year in November,

and Earth Day in April, look around and notice how many times

you see the recycling symbol displayed. With its twisting arrows

design, this symbol is recognized worldwide as the designation

for recycled and recyclable materials. It easily has the recognition

factor of Coca-Cola, Nike, and McDonald's, but do you have any

idea where it came from, or who actually designed` it?

THE STORY BEHIND THE RECYCLING SYMBOL

Because the recycling symbol is so familiar and ubiquitous, we

tend to take it for granted, not realizing that it was designed

by a real live, honest-to-goodness person who, even today, is

still concerned with the environment.

Here's the little-known story behind

the recycling symbol:

In April 1970, the very first Earth Day was held,

coinciding with an emerging environmental consciousness as the

environmental movement began to gain momentum.

One

person who participated in this first Earth Day was a student

at the University of Southern California named Gary Dean Anderson,

who designed the recycling symbol later that same year. Like

thousands of other college students across the country, Anderson

attended an Earth Day rally and environmental teach-in at his

university, which was held outdoors on a beautiful day with lots

of rock music and a mellow atmosphere.

One

person who participated in this first Earth Day was a student

at the University of Southern California named Gary Dean Anderson,

who designed the recycling symbol later that same year. Like

thousands of other college students across the country, Anderson

attended an Earth Day rally and environmental teach-in at his

university, which was held outdoors on a beautiful day with lots

of rock music and a mellow atmosphere.

Still, Anderson says there was "definitely

something in the air, in the academic community and elsewhere,

that was beginning to color everyone's image of the earth and

its resources. Neither, people were beginning to realize, was

infinite." This awareness of the earth's finite resources

and the need to conserve and renew them for future generations

continues each year as we celebrate Earth Day.

Also that spring in 1970, Container

Corporation of America, a paperboard

company, sponsored a nationwide contest for environmentally-concerned

art and design students to create a design that would symbolize

the paper recycling process.

The new recycling symbol was to be used

to identify packages made from recycled and recyclable fibers,

and to call attention to paper recycling as an effective method

of conservation of our natural resources. CCA sought to promote

greater awareness of the recyclable nature of paper fibers, and

to emphasize the contribution of recycling to improving environmental

quality.

At that time, CCA (now Smurfit-Stone

Container Corporation) was the largest

user of recycled fiber in the U.S., and easily could have had

its own corporate designers come up with the symbol, but decided

that the younger generation of students, as inheritors of the

earth, would be the best source for the new design.

More than 500 talented students submitted

their entries, which were judged by a distinguished panel of

judges at the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado.

The theme of the conference was "Environment by Design".

The first place winner was Gary

Dean Anderson, a graduate student at the University of Southern

California in Los Angeles. The second prize winner was Mike Norcia

of New York, and third prize went to Janet McElmurry of the University

of Georgia. There were also twenty Awards of Excellence presented.

The first place winner was Gary

Dean Anderson, a graduate student at the University of Southern

California in Los Angeles. The second prize winner was Mike Norcia

of New York, and third prize went to Janet McElmurry of the University

of Georgia. There were also twenty Awards of Excellence presented.

Gary Anderson had just graduated from

USC's 5-year architecture program, and was completing one additional

year for a master's of urban design. His prize for the winning

entry was a $2,500 tuition grant for further study at any college

or university in the world. After receiving his master's degree

in urban design from USC, Anderson chose the University of Stockholm's

graduate program in social science for English-speaking students,

where he studied the relationship between social interaction

and physical space, and earned a diplom in social science

(roughly equivalent to a master's degree) there in 1972. He also

had the opportunity to learn the Swedish language through the

university's intensive instruction program for languages.

HOW GARY ANDERSON DESIGNED THE RECYCLING

SYMBOL

Gary Anderson grew up in North Las Vegas, Nevada, in the 1950s.

In keeping with the times following the Great Depression and

World War II, his family practiced a general frugality that involved

re-using and recycling as much as possible, long before the recycling

movement as we know it today had begun. His family reused newspapers,

paper and plastic bags from the grocery store, and his father

either made or refinished and reupholstered much of the furniture

in their home.

As a child, this future architect built

everything from cottages to skyscrapers with his sets of plastic

American Bricks and wooden Lincoln Logs. Every Christmas, it

was his job to construct a stable out of his Lincoln Logs for

the Nativity Scene under his family's Christmas tree. He also

liked making all kinds of things out of paper - pinwheels, paper

airplanes, paper chains, you name it. An avid reader and library

user, he discovered origami in a book from his school library,

and did not stop until he had made every origami design in it

at least once.

He excelled at both math and English

in elementary school, but liked history and geography best. According

to Anderson, spelling was his worst subject in those early school

years. However, he especially enjoyed penmanship, which was taught

by the Palmer method, and his handwriting today still retains

the Palmer style. He liked the idea that even a complicated chain

of letters was really made up of just a few basic lines and curves,

each of which could be made with a simple stroke.

Later in his schooling, Gary Anderson

began to study foreign languages, art, graphic layout, and typography.

He did well in art all through school, but he noticed that there

were other students who were better at drawing realistically

and spontaneously. Some of them seemed to have "a bionic

connection between their eye and their hand that  enabled

them to reproduce exactly what they saw." He adds that when

drawing by hand, "I've always had to develop my image with

many tentative lines drawn one on top of the other, until I get

something to look more-or-less as I want it. By the time I'm

finished, it kind of looks soft and furry or hairy, even when

the object isn't that way at all."

enabled

them to reproduce exactly what they saw." He adds that when

drawing by hand, "I've always had to develop my image with

many tentative lines drawn one on top of the other, until I get

something to look more-or-less as I want it. By the time I'm

finished, it kind of looks soft and furry or hairy, even when

the object isn't that way at all."

From a young age, Gary Anderson was

intrigued by the idea of the Möbius strip, the single-sided

construction formed by gluing together the ends of a strip of

paper that have been given a twist. The Möbius loop was

discovered in 1858 by August Ferdinand Möbius, a German

mathematician and astronomer. Anderson also enjoyed the art of

the Dutch artist M. C. Escher, who produced a series of drawings

based on the Möbius strip, one of which (above left) portrays

ants crawling over the folded and twisted strip of paper.

When Anderson began designing his three

entries for the contest, he drew upon the concept of the Möbius

strip as a combination of the finite and the infinite, "a

finite object, but its one surface is infinite in a way."

He also tried to incorporate the concept of ambiguity, since

the symbol is "kind of round, but also kind of angular.

It's flat, but it seems to enclose a space ... kind of hexagonal

and kind of triangular, and kind of circular ... sort of static

and sort of dynamic."

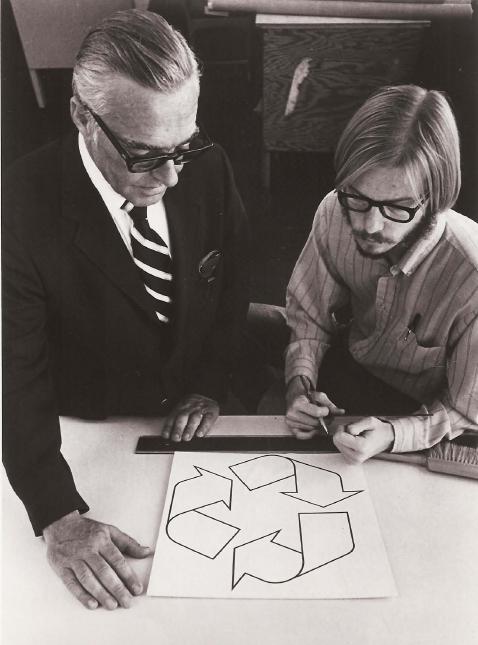

In his original design, which CCA modified

slightly to make it appear more stable, the symbol rested on

one of its short sides, implying a much more dynamic motion and

instability than the versions we see today.

Anderson drew the symbol entirely by

hand with pen and ink, without the benefit of the computer-aided

design software available to designers these days. In those days,

computer graphics was a very new field, largely experimental,

and computer-aided drafting and design (CADD) was only in the

developmental stages. And of course, no one had personal computers

either, and the computer classes offered in college were all

taught using mainframe computers and punch cards.

Graphic design at this point was essentially

limited to arrangements of different combinations of alphanumeric

characters distributed across a tractor-fed page. Anderson says

that, "If we were writing a program - and you had

to write a program to create a computer generated image - you

had to leave a stack of punched cards off at the computer center

at night, and pick up the output the following day. Every time

you did this, you hoped you had finally gotten all the bugs out

of your program, and that what you got back from the computer

center was what you actually wanted."

The

design process for the recycling symbol went quickly for Anderson,

especially since he had been mulling over this type of image

for some time, and had experimented with several different configurations

for class projects in architecture school. He worked out his

clean and simple series of designs over a period of only two

to three days. Looking back, he feels that his designs were influenced

not only by M. C. Escher's art and the Möbius strip, but

also by the wool symbol, reminiscent of spinning fibers, and

the concept of the mandala as a symbol of the universe in the

Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

The

design process for the recycling symbol went quickly for Anderson,

especially since he had been mulling over this type of image

for some time, and had experimented with several different configurations

for class projects in architecture school. He worked out his

clean and simple series of designs over a period of only two

to three days. Looking back, he feels that his designs were influenced

not only by M. C. Escher's art and the Möbius strip, but

also by the wool symbol, reminiscent of spinning fibers, and

the concept of the mandala as a symbol of the universe in the

Buddhist and Hindu traditions.

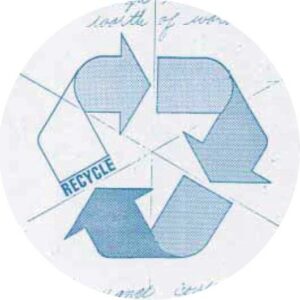

The one (and only) sketch of his recycling

symbol that survives (shown above) is the most complicated of

the three designs Anderson submitted for the contest. This working

sketch of the recycling symbol design appears in a letter home

from college to his mother. Note that this design is resting

on one of the arrows, in contrast to the version modified by

CCA. The design picked by the judges as the winner was the simplest

and plainest of the three, with no words or shading on it, and

his third entry was something in between. Container Corporation

of America did not trademark the symbol, thus leaving it in the

public domain. For this reason, many permutations of the original

design have been developed over the years for a wide range of

purposes.

Interestingly, it took a number of years

for the recycling symbol to catch on and become widely used in

the United States and elsewhere. In fact, Gary Anderson had seen

it only rarely before seeing it prominently displayed on recycling

bins in Amsterdam while travelling in Europe some ten years after

he had won the contest.

GARY ANDERSON'S LIFE TODAY

More than thirty years later, Anderson is still involved with

environmental issues. As the winner of the recycling symbol contest,

he could easily have pursued a career in graphics design, but

his career goal remained urban planning and design. Over the

years, he has been employed in various capacities as an architect

and planner, and has won numerous academic and professional awards

for his projects. He has authored many professional reports,

technical reports, and conference papers.

After receiving his doctorate in geography

and environmental engineering from The Johns Hopkins University

in 1985, he joined the firm of STV

Inc. in Baltimore, Maryland, where

he served as Vice President and Technical Manager of the twelve-member

Planning Department.

In March 2004, after 18 years at STV

Inc., Gary Anderson took a position as vice president at TEC

Inc. (The Environmental Company) in Annapolis, Maryland. TEC

Inc. provides architect/engineering environmental consulting

to public and private sector clients.

A self-described "dreamer, doodler,

and putterer," Gary Anderson is also goal-oriented, enabling

him to move ahead and complete real projects. He enjoys his frequent

travels abroad for his work, having had planning projects  in England, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and

Turkey, where he often teams up with local companies to work

on joint projects. Over the years, he has been a guest lecturer

at workshops and seminars in Turkey and Italy, and has authored

numerous professional technical reports and conference papers.

in England, Belgium, Germany, Italy, and

Turkey, where he often teams up with local companies to work

on joint projects. Over the years, he has been a guest lecturer

at workshops and seminars in Turkey and Italy, and has authored

numerous professional technical reports and conference papers.

In addition, he has taught architecture

and planning courses in Saudi Arabia, and currently teaches a

course at The Johns Hopkins University. He is active in his local

civic and neighborhood improvement associations, and is a member

of several Baltimore museums. He sits on the board of directors

of 1,000 Friends

of Maryland, a managed-growth advocacy

group.