Stuart Givens teaches Canadian and European History at Bowling Green State University, and has for over 45 years. His white thinning hair and thick spectacles give him a grandfatherly air. He has a self-assured and leisurely manner of speaking. His office is filled with not only the expected history books but miniature British soldiers from various eras and a wooden model of a World War II glider.---Jonathan Crow

Interviewer: Where were you when you heard about Pearl Harbor? What was your reaction?

Givens: Well, this is kind of interesting in a way...I was a senior in high school and I was in a club. It was a hiking club which was organized by my biology teacher. We were on a weekend retreat up at Catoctin State Park [Roosevelt's "Shangri La"] which is now known as Camp David. We didn't hear about [Pearl Harbor] until we were on our way home. We turned on the car radio. So I was at Camp David during Pearl Harbor.

I was surprised, of course. We'd been talking about war and the possibility of war and what should the United States do in terms of the war for two years at that point. We had debates in high school and constant discussion of what our role should be. I was pushing for increased support for Britain. By the time of Pearl Harbor, the attack on Russia had already occurred. So, it was a shock on the one hand but it was kind of anticipated that we'd enter the war.

I: What movies do you remember from the war?

G: I don't particularly remember any but I saw them all. (Laughs) While I was in training during a year and a half, while I was in this country, there were about three movies a week that were shown at the camp movie theater. It was one of the few things to do aside from reading for me. I wasn't a big party guy...I didn't go tearing out of camp on weekends. So I literally saw every film that came out during that period. I was so inundated that I haven't any particular recollection about any of them.... I remember Private Snafu and Situation Normal: All Fouled Up.

I: Did you see any of Frank Capra's Why We Fight series?

G: I don't think I saw any of them or at least I have no memory of them. What I saw were the regular commercial films. The only films that the army showed, that I recall seeing, were primarily Russian army combat films. They were somewhat propagandistic, but we saw them to see what the Russians were doing and how they were fighting. I know about the Capra films, read about them since, but I don't remember ever seeing them.

I: When you were shipped out, where were you shipped to?

G: Well, originally we went down to Camp MacKall, North

Carolina, which was still being built. When we got off the train we were

informed that we were a part of a brand new division that was being formed

which was the 17th Airborne division.

I: What kind of training specifically did you do?

G: Oh, we worked on gliders, flew around in gliders, but that was a

small part of [my training]. Most of the time, we had physical training.

I lost, during that summer, close to 45 pounds. We ran first thing in the

morning and an hour every afternoon, then we had a lot of training in rules of

war and first aid. We spent half the day practicing on the anti-tank

guns....There was a lot of physical work involved.

I: What did you do during your free time?

G: Well, I went to movies (chuckles). During the summer there was a big lake on the reserve, though it was out a ways. Some of us would walk out there. Went swimming, went to movies, read. I read from cover to cover, sometimes twice, Readers Digest. It's not that great or that intellectual but it was available. As I said, lot of people got passes and went out to town. I did that occasionally, but it wasn't my bag. So I stayed mostly on base. There was a beer garden there but I don't drink so that didn't help either. (Chuckles.) But I sometimes went there with my buddies, we'd sit and talk.

Following winter maneuvers in Tennessee, in the beginning of 1944, Mr. Givens was shipped to Camp Forrest where he was enrolled in paratrooper training.

I: What was your training like? How did you feel to jump out of an airplane?

G: Scared. (Laughs.) The first jump, well they loaded you in

willy-nilly. We were jumping out of C-47s which had twelve seats on

one side and twelve on the other. The first person in was number

twelve, who was also the last one out. I ended up being number

one. The fellow next to me was an officer, I was an enlisted man. He

kept saying, 'Are you sure you can do it soldier?' and 'Aren't you

nervous?' and 'Relax, don't worry about it.' (Laughs.) I wanted to

say 'Please shut up sir' but I didn't.... I remember that

[particularly] because it was the only time I was number one, so I was

standing at the open door, the landscape going by and then they gave

the signal to jump. And I did.

The third jump, I badly twisted my ankle. Some of the terrain for the landing sites wasn't so good, so I was off my feet for about four days. Eventually, after about a week or so I was good enough that I could jump again. So the fourth jump I was nervous about it because of my ankle. And in that particular time I was number eleven. We got down and started going out the door. I did have some apprehension. The nine went out and when we got to number ten, he froze in the door. So finally, the jump sergeant just kicked him out the door. (Chuckles.) By that time, we were past the drop zone so we had to go around again, just for two of us. So when we got back around for the second time, the guy behind me quit. Didn't want to jump. So I was it. But that went OK. And then the fifth jump. The first four were daylight jumps. The fifth one was a nighttime one. Then after that we were shipped out.

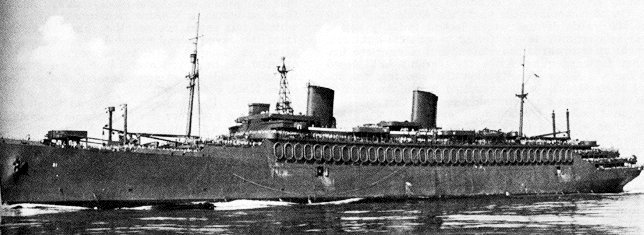

After that we went up to Camp Myles Standish in Boston which was a staging area. One thing that I remember clearly is that we went through Washington [where Mr. Givens spent much of his childhood] on the train during a sunny afternoon. We slowly went through town and I was standing there looking at my hometown and my parents were there. We kept on going through, but that particularly struck me. But anyway, we were at Camp Myles Standish for three or four days and then we were loaded on a liner previously named the US Manhattan, but now called the USS Wakefield.

From Liverpool, we were transported to Wiltshire, down near Stonehenge in early August [1944]. We were the only American division in England -- everybody else was over on the continent. Starting from late December we were in the Battle of the Bulge for about five weeks, and then we were pulled out of the line and went back down into France. On the 24th of March we were involved in Operation Varsity, which was an airborne attack across the Rhine in cooperation with the British Army under General Montgomery. We were the only American unit: everything else there was British.

This leads into the occupation. The 17th Airborne shipped all the people eligible to be released home. About half of those left over were transferred to the 101st who also went back to the States. The other half of us, approximately, were put into the 82nd Airborne, which, after more training, joined the occupation forces in Berlin. We were in Berlin from August of 1945 until the end of the year; at that point the 82nd was shipped home on the Queen Mary in order to take part in the Victory Parade in New York City on January 6, 1946. There was ticker tape and the crowds...it was an absolute thrill. A capstone, perhaps. Soon as that was over I was shipped back to Fort Meade and I was mustered out. It was just about a three-year cycle.

I: What were your living conditions during the Battle of the Bulge from day to day?

G: Well, we were out in the weather most of the time. Occasionally, we would take over a house at night. A lot of times though, we'd just try to dig a hole -- the ground was frozen so you couldn't dig very much -- and sit down and try to sleep.... It was snowy, it was cold. But we got hot food most of the time. Other than that, we were looking for the enemy or chasing the enemy, fighting the enemy. We had some pretty good exchanges of fire between the two sides. But...it was a daily kind of thing.

You really had no idea what was going on in the larger picture. We just knew that we were here and that the Germans were over there. Sometimes you saw them and sometimes you didn't. Eventually, we began to realize that we were making progress and that they were retreating. But we didn't know on a daily basis what was really happening and certainly not what was going on someplace else.

I laughed once when I was watching CNN -- some of the soldiers stationed in Bosnia said that they hadn't had a shower in four days or something like that. Well, [during the Battle of the Bulge] I had a shower sometime before I left England, sometime before Christmas at least, and the next time I had a bath was about three months later. In the same clothes. In my case, as with a lot of others, there were some stomach upsets and diarrhea. I tried to clean that up as best as I could, but my clothes were somewhat soiled and more than that -- smelly. But then everyone else was smelly too. You've seen the Willy and Joe cartoons, we looked pretty much like Willy and Joe. It was plain, basic living. You'd get shot at every so often and you'd shoot back.

I: You didn't get wounded, did you?

G: No, I didn't. I was fortunate. (pause) I had some close calls, but..(chuckles) But nothing in either the Battle of the Bulge or in Operation Varsity. Nobody in our platoon was killed. We had a number of wounded and two who went off the deep end. We began with 36 and by the end of the Battle of the Bulge we were down to about 20. But none of them were killed, fortunately.

I: Did you have problems with frostbite?

G: Yeah, a minor case. To this day, when it's cold out, I have to wear gloves or I suffer from excruciating pain.

I: Between the Battle of the Bulge and Operation Varsity, in which one did you see the most combat?

G: Actually, in Operation Varsity I personally saw more action. In the Battle of the Bulge we saw a lot of really heavy fire for the first couple of day and then after that the Germans were retreating slowly. We had some firefights but by and large they were just retreating and we were following them. The first day particularly was bad.

In Operation Varsity, because we were behind enemy lines there was a fair amount of exchange there, along with anti-aircraft guns and anti-tanks guns. If you were to equal it out in terms of actual shells flying, that sort of thing, it's Operation Varsity. In terms of discomfort, it's the Battle of the Bulge. Operation Varsity took place between March and April and by that point the weather was actually pretty decent. So at least we didn't have that discomfort. Of course, we were still being shot at and we were still shooting back.

I: How did you feel when you were in a combat situation? Were you terrified?

G: No. That's an interesting development that I was aware of at the time and it's something that I talked about and read about since. There are two kinds of people involved in [war]: those who worry about what's going to happen to them and then once they get into the circumstance become quite calm; on the other hand, there are the ones who say 'I can't wait to get there' and all that and then they get there and they panic. I was in the first category. My stomach was upset and I lost my appetite. I was worried, particularly when I was in Camp Myles Standish before I even got on the boat. But in combat, I was as calm and cool as a cucumber. This doesn't mean that I was standing up in the trenches, but I was really very calm. On the other hand, this guy from Kentucky in our outfit who was saying 'I can't wait to get my hands on those Jerries' and all that. On the first day, when the firing started, he got up and ran. He just panicked. And he was one of the ones that couldn't wait to get into combat. I'm sure there were all kinds of variations in between but combat really didn't bother me at all.

I: How did you find Berlin during the occupation?

G: It was devastated. There was hardly a block that didn't have some damage. I mean block after block after block was just gone. Completely ruined.

While I was there, about twenty percent of [my] division was made into honor guards. And I happened to be one of those, which was interesting because every time anybody of note came into Berlin, if they landed in Tippelhoff [the main airfield in the American sector of Berlin] at least, there was always a review and parade. I got to see many of the major figures in World War II in one form or another. So I got to see Eisenhower, Montgomery and Russian general Zhukov. I also saw Patton too, but that was during the Battle of the Bulge. He actually bawled out eight of us for not wearing our helmets.

And also, this is kind of humorous, our higher-ups said that there was no paper work of us doing glider training. Of course, when I went into combat across the Rhine, I went in a glider. But they didn't have the record of this, so we had to do glider training. Our indoor glider training was on the sound stage of the major German movie studio in Berlin. But it got us off guard duty for a while so it wasn't all that bad. And then the best part about it is that we had to do flight training. So we'd have to go up flying over Berlin area and see it all from the air. And then of course the war was over so the atmosphere was less serious and some of the people I was with, well, they were a bunch of cut-ups. One time, we were flying around, I didn't even think we could do it, but we did a loop to loop. There were no seatbelts so we were just holding on. (Laughs.) That was pretty thrilling. And then we'd go into stalls, we'd dive down and then at the last minute pull up. So we had some thrilling rides there.

I: How did you find the Germans during the occupation? Did you have a lot of contact with them?

G: Quite a lot. They were all pretty friendly and cooperative. Before we had gone to Berlin, we had trained in the Vosges mountains in riot techniques, so we were expecting something, but we found them some of the nicest people you'd ever want to meet. Maybe under other circumstances, they might not have been that receptive, but.... We didn't see too many males, mostly females and infants. And they were all very friendly. The younger women were very friendly. (Laughs.) Fraternization, which was not supposed to occur, was pretty broadspread. Literally, in my platoon, I was the only person who didn't have a German girlfriend....I had a girlfriend at home. I'm old-fashioned. (Laughs.)

The ones we had the strangest relationship with were the Russians: part of it was language but they pretty much kept to themselves, or they were kept to themselves. We could roam all over, so we'd roam into the Russian zone and the British zone. Rarely did I see a Russian soldier or soldiers except on some kind of official duty of some sort. Ever. So it was all very formal and a little cold. They weren't unfriendly but it was kind of a stand-offish relationship.

I: When you were in combat, what were your feelings towards the Germans?

G: Well....it was kind of like being in a tournament in basketball. We'd want to beat them and if we don't they're going to beat us, and we don't want that to happen. Of course, being 'beaten' means getting captured or shot. But I wasn't conscious of any feelings that they were bad guys -- someone that we should kill because they were bad guys. But they were the enemy and they were being ordered to shoot at us and we were ordered to shoot at them.

I: Where were you and how did you feel about the bombing of Hiroshima?

G: We were in Berlin. Like most veterans...well, there were two factors there.... One, we didn't really comprehend the magnitude of it. We just knew it was a super bomb and that it was bigger than anything that had been used. And then secondly, even though we were in Berlin, we knew that we were going to end up being involved in an invasion. Our reaction was anything that could end the war and lessen American casualties was good. Now we said that not knowing anything about the radiation.

I: Has your view towards Hiroshima changed at all?

G: No. I still think it was the right decision. Well, actually, after a few weeks we started getting more information about it, especially after Nagasaki, I thought that at least for the first one that we should have in some way demonstrated the power of this weapon, and see if that wouldn't make them surrender. What I didn't know at that time was that we only had two bombs, and it would have taken a long time to build more. But when I heard about the devastation...there were so many casualties, I wonder if they couldn't have picked a less populated place. At least for the first one. But, I understand why they did what they did. I still felt, I mean it's horrible -- I don't mean to dismiss the horribleness of it but when you look at the [number of] deaths in Hiroshima or Nagasaki, they were both less than the fire bombings over Tokyo or the bombing in Dresden. Hiroshima was technically a military targets. Of course, that wasn't why it was dropped there, but in Dresden there was nothing. That wasn't a racist decision, because they were killing white Europeans -- it was just senseless. But at the time we thought, anything that would bring the war to an end...and you look at what had happened, you look at Iwo Jima just before, which I think that the people in charge had to work from, the assumption that the Japanese military forces and leadership was going to continue to fight the same way they had, where the casualties were really high on both sides.

I know the moral issues and I'm not unconcerned with them. But to save 10,000 or 100,000 American lives and probably the same number or more Japanese lives-by killing 100,000 or 50,000 Japanese-as opposed to many more Japanese.....then I'm [pause] for saving lives, American lives. I'm still not convinced that firebombing is not as horrible and not as immoral as the atomic bomb. One bomb does more but in terms of what it does and the damage and fatalities... it's a stand-off at best.

I: Two years ago there was a big flap over the Smithsonian exhibit for the fiftieth anniversary of the bombing. When you heard about it what was your reaction?

G: Well, appearing to be disloyal to my profession, or parts of the profession at least. (Chuckles.) Both my historian nature and certainly my veteran nature comes out and I think, the way I've read about it and understand it, I may not know all the facts but from the looks of it, I think that the original display...well, I just disagreed with it.

I think for a commemoration of that -- and this is where a lot of historians disagree and I disagree with a lot of historians -- I think you need to portray an historical event accurately in light of the times and in the attitudes of the time and not in terms of some later interpretation. If you're going to show the bomber, or part of the bomber, then it should be shown in light of what it was and in light of why it was done. And not to dredge up moral questions. Now there's a place for that too, but since [the exhibit] was in commemoration of that event, I don't think that the morality issue should have been a part of it. A lot of innocent people were killed and maimed and to point out some of that is fine but it seems that the more I read about it, I started to resent [the exhibit].

I: How have your views towards the war and memories towards the war changed over the years?

G: Well, I don't know. Other than the obvious...as time passes you remember the good and tend to forget the bad. Although, I didn't forget all of the bad.

I do have a 50 caliber machine gun bullet on my dresser. Sometimes I wonder why I have it there. Not every time I look at it, but a lot of the time when I look at it I think about a dead German soldier that I saw along the road who was shot in the head by a 50 caliber bullet.

Another story along those lines, it was probably 1948 or '49, I saw a movie called Battleground. At that point, I'd seen a fair number of movies about the war and this was about the Battle of the Bulge. Anyway, my wife and I went in there to see the movie, this was in Palo Alto, California, while I was [studying for a PhD] at Stanford. We were newlyweds so we were holding hands. Half way through the battle scene my wife leans over and says "You're hurting me." I wasn't conscious of it, but I was clamping down on her hands so hard that it was painful to her.

Another thing, if you're talking about the impact [of the war] I am horrified...I shudder at violence. I don't like any kind of violence. I can't watch war movies anymore. It just...just bothers me emotionally and I really do attribute that to the war. I don't want to sound over-melodramatic, but...I haven't had any nightmares or those things you read about...but I've seen enough of that sort of thing and I don't want to see anymore.

I: You have a lot of toy soldiers around in your office. Is this for historical reference?

G: That's all history. I teach British history and those are all British soldiers. I mean I enjoyed my experience...I don't want to make a career out of it, but I like reading military history. I don't consider myself a militarist in any sense of the word but I'm not anti at all either. So I have these soldiers...I also have some war souvenirs. Things that I have up in storage.

I: What kind of souvenirs?

G: Well, I have three German daggers with the swastikas on them and a whole bunch of swastika arm bands. I got a German swastika flag that I found, I can't document this so you'll have to take my word on it or don't, but I found it going down the stairs in the bomb shelter of the Reichstat. Why it had been there I had no idea: it been there for months or more. It was the worse for wear. It was torn and riddled by bullets, or at least that was the way it appeared.

I: What was your reaction to later wars like Vietnam or the Gulf War?

G: Well, I guess generally I've been in support of the war, though I was less supportive of Vietnam as time went by, like a lot of other people. I don't particularly like war, but I would really say that World War II was the justifiable war.

Links: