|

|

WELL FACTSHEETEcological Sanitation Authors: Jo Smet and Steven Sugden, April 2006 Quality Assurance: Sandy Cairncross Ecological sanitation - What is it? Eco Sanitation works on the principle that urine and faeces are not simply waste products of the human digestion process, but rather are an asset that if properly managed can contribute to better health and food production and reduce pollution. Eco-sanitation latrines:

Since

early Chinese history, human excreta was commonly

used in agriculture to complement farm manure in

improving soil fertility. Farmers owned

‘Outhouses’ where they invited visitors to leave

behind their ‘valuable’ excreta. In

early Europe, Greek and Roman societies collected

human excreta and used it as fertilizer. The Romans

found that urine contained high value

nutrients and collecting it was a good business.

Emperor Vespasian introduced a ‘urine tax’ along

with the proverb pecunia

non olet (Money does

not smell). In Britain, Queen Victoria used an earth-closet at

Windsor Castle, although many types of water-closet

were available. Henry Moule in 1840’s was the

champion of the earth-closet and backed up his

belief with a scientific experiment where he

persuaded a farmer to fertilise one half of a field

with earth from his closet, and the other with an

equal weight of superphosphate. Swedes were planted

in both halves, and those nurtured with earth manure

grew one third bigger than those given only

superphosphate. For

many years, the earth- and water-closets were rival

systems with champions and detractors on both sides. The nutrition value of urine and faeces as fertilizers

(500 litres of urine and 50 litres of faeces are about the amounts produced by one adult in a year) Note that most of the nutrients are in the urine, though the vast majority of the pathogens are in the faeces. Although faeces has a lower nutrient content, its high organic matter aids water retention and is a good soil improver.

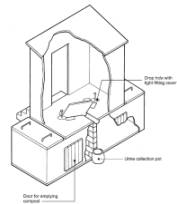

Fig1: Nutrients for plant growth present in human faeces and urine Ecological latrines can be divided into two main types: (i) dehydrating urine separating toilers and (ii) composting toilets. (i) Dehydrating urine separating toilets The urine and faeces are collected and stored separately by the use of specially designed pedestals and slabs.

Fig.2 Dehydrating latrine with urine diversion and the principle of a urine diversion latrine The urine is collected and stored until it can be used

as a fertilizer on plants or crops. The faeces drops

into a pit, vault or container to which a handful of either ash or

lime is added. This has the effect

of drying the faeces and increasing the pH which has

a positive impact on reducing smell (less ammonia

emission) and destroying

pathogens (see GTZ-EcoSan Datasheet-2).

After 12 months of storage the resulting

‘humanure’ can be applied to the land. Some form

of alternating double or multiple storage system is

required to avoid mixing fresh and composted manure. (ii)

Composting

toilet The double-pit or vault composting latrines do not

separate the faeces and urine, so that both

enter the same vault or pit. A handful of a mixture

of soil and ash is added to the pit after each use

which has the effect of keeping the pit contents

relatively dry and aerobic, as opposed to anaerobic and

smelly. ‘Composting’ is not technically the

correct name as the temperatures never rise high

enough to create themophilic composting conditions.

After 12 months of storage the resulting

‘humanure’ can be applied to thet land as a

fertilizer and soil conditioner. The simplest form

of composting latrine is called the Arborloo or

‘walking latrine’ (see below).

Fig3: Arborloo as introduced in Southern Africa

Reasons to adopt ecological sanitation In

many Developing Countries poor soil fertility and

the increasing cost of artificial fertilizer is

making it difficult for subsistence farmers to grow

enough food to feed their families. Survival becomes

more perilous as population growth means new land to

cultivate is not available. The fertilizer producing

qualities of ecological latrines can help the

household economy of poor families as demonstrated

by the following comments collected from Malawian

farmers who have been using eco-sanitation for a

number of years,

In their testimony, these farmers allude not only to the nutrient quality of the ‘humanure’, but also how the organic matter from the faeces improves soil structure. The

act of adding ash and/or soil and separating the

urine has the effect of drying the faeces and the

possibility of pathogen transmission to the water

table is eliminated. This makes eco sanitation a

particularly good option in areas where

contamination of groundwater is a sensitive issue. In

water stressed or arid areas, ecological

sanitation (which needs no water for flushing) can help save this valuable resource.

In the developed countries of

the north it has been estimated that use of

ecological sanitation could reduce domestic water

consumption by 20-40%. Conventional

sewage systems effectively remove faecal material and the

pathogens it contains from the immediate household

and community environment and deliver it to a sewage

treatment works. In many countries the sewage works

are incapable of effectively treating the waste as

the volume entering the plant exceeds its design

capacity (either because of population growth, the

high cost of electricity or the

mixing of sewage with storm water). The result is

that poorly treated sewage is discharged into

streams and rivers with detrimental effects on the

rivers' flora and fauna. It is argued that if

eco-sanitation was more widely used, the need to

build and operate expensive sewage works would

diminish and the water quality in the rivers would

improve. In

developing countries, areas with high groundwater

tables and collapsing sandy soils are notoriously

difficult in which to build permanent traditional

latrines. Ecological

latrines with their shallow pits or vaults can

provide good, sustainable affordable solutions. Faeces

in all cultures is regarded as disgusting

and to

many people, the thought of using it for

food production is

repulsive. In addition, many cultures have

strongly-held beliefs and taboos regarding faeces that make

ecological sanitation unworkable. This

avoidance

instinct has self preservation at its heart

as

faeces contains many pathogens that are

harmful to

man if ingested. Even where there is no risk

of

disease transmission, the cultural

perception may be

different as demonstrated by this Malawian

farmer:

“If I eat crops and fruit grown in my own excreta, it can provide

disease”.

People

generally prefer toilets where faeces cannot be seen

and where no further handling by the users is

required. With a water closet the only necessary

further user action is the pulling of a handle; out

of sight out of mind. With eco-sanitation there is

always some form of secondary handling of the faeces

and user reluctance to do this could be high. Even

if an individual is willing to adopt eco-sanitation,

they may be put off from doing so by the fear of

being ridiculed by the rest of the community.

Sanitation systems are one of the key defences in breaking the faecal-oral transmission routes of many diseases. The capacity of a latrine to either ensure no further human contact with faeces or to reduce the pathogens to safe levels is an essential prerequisite. With ecological latrines, their ability to perform the latter is questionable. The potential health risks associated with ecological sanitation Ecological latrines use the following techniques to ensure pathogens die off:

Ascaris is the most persistent pathogen in

faeces and is therefore used as an indicator of

pathogen removal efficiency. In a well managed ecological latrine where one or a

combination of the above environmental conditions

has been acgieved in

the pit or vault, Ascaris eggs will be reduced to a level where they do not present

a risk to public health. Problems arise when the

latrine is not well managed and the user has either

misunderstood or does not followo the management

regime stipulated by the designers. Unfortunately

this is common and is one of

the major weaknesses of ecological sanitation. However, pathogen destruction in ecological

sanitation is often viewed from the negative angle

of what it does not achieve with regard to Ascaris

die-off, and never from the angle of what it does

achieve with a whole host of other pathogens. Ecological latrines, where

storage times are greater than 3 months, will reduce

to safe levels the pathogens responsible for Ameobiasis, ,

Giardiasis, Hepatitis A, hookworm, Trichuris

(whipwork), Enteribius

vermicularis (threadworm), Hymenolepis

nana, Rotavirus, Cholera, Campylobacter,

Eschericia coli, Salmonellosis, Shigellosis and

Typhoid. The debate about the safety of ecological sanitation often occurs in isolation of the context in which it is being practiced and the larger question of whether the introduction and practice of ecological sanitation will improve the overall health of a community is never addressed. Generally speaking, from a health perspective an ecological latrine is better than no latrine at all and any possible health risks must be weighed against the potential improvement in the household economy and a family's ability to feed themselves. Ongoing

research and learning on EcoSan

Research,

demonstration and full-scale programmes are

financed by many Southern and Northern

governments and organizations. Some major

donor-supported programmes are GTZ EcoSan (www.gtz.de/ecosan),

Sida-supported EcoSanRes (www.ecosanres.org).

The websites give also reference to

other ongoing research. Three international

EcoSan Conferences/Symposia have been

organised (China, Germany and South Africa).

Home > Resources > Fact sheets > Public Private Partnerships and the poor |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||